After a summer in BC, a short stint in Bellingham and Northern California, we are stationed along the central California coastline. We quickly took to walking the nearby golden hills in search of any remaining wildflowers still miraculously blooming despite the ongoing drought conditions. What became quickly apparent to me was the overwhelming main colors out and about were yellow or purple-colored petalled flowers. But why?

The flowers I saw in late September/ early October included, but weren’t limited to:

Yellows:

- Bush Poppy (Dendromecon rigida)

- Dunedelion (Malacothrix incana)

- Common Hareleaf (Lagophylla ramosissima)

- California Goldenbush (Ericameria ericoides)

- Clustered Tarweed (Deinandra fasciculata)

- Threadleaf Groundsel (Senecio flaccidus)

- Southern Goldenrod (Solidago confinis)

Purples:

- Vinegar Weed (Trichostema lanceolatum)

- Silver Rock-Lettuce (Stephanomeria cichoriacea)

- California Aster (Corethrogyne filaginifolia)

- Santa Barbara Wirelettuce (Stephanomeria elata)

- Crisp Monardella (Monardella undulata crispa)

- Santa Barbara Ceaothus (Ceanothus impressus)

- Alkali Heath (Frankenia salina), Red Sand-Verbena (Abronia maritima)

- Roundleaf Leatherroot (Hoita orbicularis)

This initial observation is a couple weeks old, and now I see another color has entered the mix, red. Red is coming from California Fuschia (Epilobium canum) and Cardinal Catchflies (Silene laciniata), along with a few Paintbrush species. But I’m not talking about red flowers in this post, it’s all about yellow and purple today folks! What causes these colors? What are the differences between yellow and purple? What pollinators visit? Why mainly these two colors on these landscapes?

To start off. . .

Color is created by the pigments within the petals, or what most people recognize as petals. Plants are funny beasts sometimes, and today we aren’t going deep on botanical terminology. Anywhoo, pigment is simply a molecule with a unique molecular structure.

If the molecular structure changes, like adding or losing a Hydrogen molecule, the color will therefore change. Are flashbacks of high school chemistry flowing into your mind? It’s okay, this is simple and fascinating. Simply, the number of hydrogen molecules within a pigment will determine the color we see. In solution purple petals are bases, they like to accept Hydrogen ions, whereas acids like to donate hydrogen ions. So when conditions change or an acid or base is added to the petal, it will change color.

These pigments of course have their own special names. For purple, these pigments that produce the purple coloration are anthocyanins, member of the flavonoid group. Whereas for yellow, the pigments are carotenoids. You’ve probably heard of chlorophyll. Uhhh duhh, you may be thinking. That’s the pigment in plant structures that appear green to our human eyeballs, like leaves, stems, phyllaries, etc.. Yes, yes, recall all that color really is, is the reflection of that wavelength of light.

Basically:

- Carotenoid → yellow petals

- Anothocyanin → purple petals

Anthocyanins can provide protection against light exposure, kind of like sunscreen for humans. I touch on this in a post about some purple cacti I saw in Anza Borrego Desert earlier this year.

If all this talk of plant collaboration is making you think about fall, a year ago I wrote a blog post about the unique fallen leaves I stumbled upon on my naturalist hikes. If interested in fall colorations in leaves, take a read here.

Color and the pattern of colors of course are a signal to pollinators. It can be both a “hey bee, get over here I got sweet juicy nectar for ya,” or it could say “hey wasp, don’t worry about visiting me, I’m past my prime.” The former scenario touches on the fact that petals will change color throughout their lifespan, and can signal that to their visiting pollinators. For our purple petals that means the quantity of anthocyanin produced changes over time, altering the color intensity. Secondly, acidity can fluctuate over time which changes the hue, defined as the true pigment. The vacuole, a cell organelle whose function depends on the cell type, can change the pH of the petal in flowers. As concentrations change across the vacuole, the level of metal ions affects the pH, like iron or aluminum fluctuate, therefore altering the color.

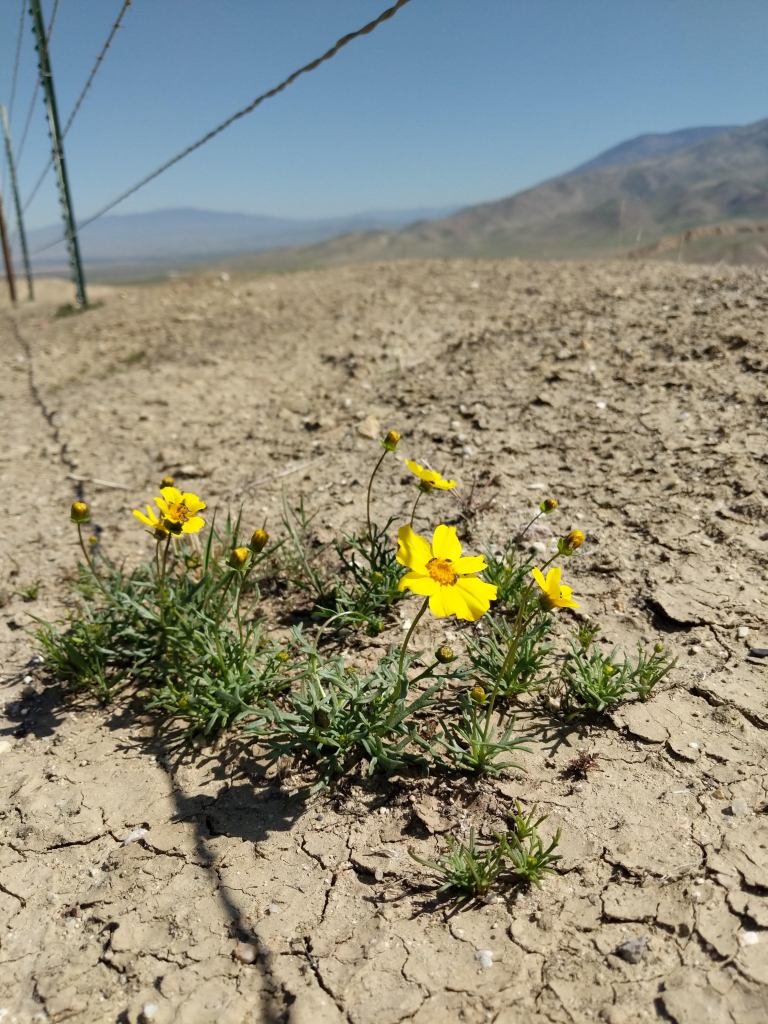

Mojave Desert, CA

Bear Valley Springs area, CA

Mountain Harebell, Ramose Ridge, BC

Southern California

Of course, within a species, individuals can have quite the variation in pigmentation, within one population or across their whole range. In terms of differences within a specific color, a study of tree peonies by Qianqian Shi et al. in 2018 explains another aspect of what determines the colors we see.: “reports have indicated that the petal epidermis cell shape can affect flower color. Conical cells lead to darker flower colors and improved color saturation. In contrast, flat cells lead to lighter flower colors.” Going one step further, from the same paper: “differences in the shape of the petal epidermal cells also affect the texture of petals and ultimately affect pollinator attraction (Glover,2000). “

Of course, flower coloration isn’t for us humans to care about, it’s for the pollinators! Butterflies are attracted to many-colored flowers, including purple and yellow. Bees like to frequent yellow flowers, picking up the pollen in exchange for nectar. Hummingbirds are attracted to yellow, as long as the flower is receptive to the hummer’s anatomy. Flowers with stripes on the petals (often seen with purple flowers) actually helps lead pollinators to the flower’s desired destination, generally the center–where the goods are. These stripes are called nectar guides.

Yellow Sand Verbena

Desert Sand Verbena

So why exactly there are so many late summer/early fall purple and yellow flowering plants in Central California still remains a bit of a mystery, as I couldn’t find an answer. I wasn’t looking for one reason to explain this observation, and as is with most things in nature, it’s complex. Many many factors influence what we humans observe when we go galavanting in natural ecosystems. Perhaps there’s an answer out there to be discovered by a Masters, or PhD student. That ain’t going to me folks, but I’ll gladly read future papers on this topic.

But being a naturalist is all about being curious and asking questions like this one, and proposing ideas that may be total garbage. So here are my ideas:

- The pollinators still around have co-evolved with these late summer blooming plants.

- This pigments are less water demanding than others, since these bloom when water in central and southern california are at it’s lowest point.

- It’s advantageous to have the purple and yellow wavelengths of light because they may be easier for pollinators to find amongst all the golden/beigey tons of the grasses.

- Maybe I’m missing a common theme about petal or root morphology that these plants posesses, perhaps drought tolerance and hardiness that color is just a byproduct

What are your thoughts? Any ideas on why I saw mostly yellow and purple flowers in late summer in central CA? Or am I just crazy? Leave your thoughts in the comments below.

- Resources:

- Shi, Qianqian, et al. “Morphological and biochemical studies of the yellow and purple–red petal pigmentation in Paeonia delavayi.” HortScience 53.8 (2018): 1102-1108.

- Moyroud, E., & Glover, B. J. (2017). The physics of pollinator attraction. New Phytologist, 216(2), 350-354.

- Science Friday: The Color of Flowers

Hi Chloe , You are so smart ! Again , I learned so much from this blog . I think pollinators are like planes landing. The pollinators land on a stripe flower petal like a plane landing on a runway strip . I think the pollinators have had to adapt to new environmental conditions that are drastically changing and I think that is incredible. I may be off here but hydrangeas change color based on the acidity of the soil or base . Thank you Sweetie for another great blog xxxxxxooooo

love Moma

>

LikeLike

Yes, what a great connection to color changing hydrangeas!

LikeLike

Hey, in color theory, purple and yellow are complementary colors, so if you mix them you will get a flat color (brownish), but if you put them right next to each other they appear brighter (painters use that trick a lot, see Van Gogh). Maybe it is an evolved feature to appear more visible from a distancie.

LikeLike

You make an excellent point! I have been meaning to go back to this blog and explore color theory, as I didn’t think of it when initially writing this post, you’ve given me a great reminder nudge to do so! Much thanks for reading the post, and leaving this comment!

LikeLike